As biologists who teach genetics and evolutionary biology, we’ve been discussing the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in our classes for the past year.. Fortunately, our conversations with students are turning cautiously optimistic: their grandparents and our parents have gotten one or two doses of the vaccine, and many of our students who work in health care have as well. At the same time, our optimism is cautious: new variants of the virus are appearing in the news, and several appear to be increasing in the U.S.

The New Variants: UK and South Africa (and Brazil and New York and California . . . )

The virus causing COVID-19 has been mutating from the beginning, as viruses do. While most of these mutations will not help a virus survive in its host or infect a new one, some will. However, the thinking a year ago was that mutations in the coronavirus shouldn’t be a problem as its mutation rate was much lower than for influenza.

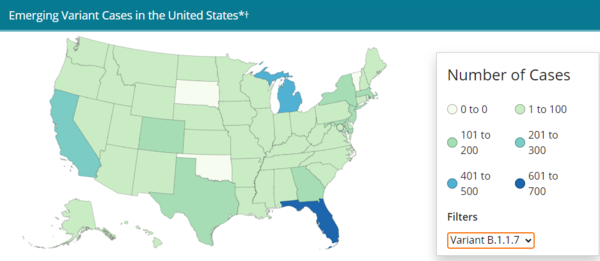

Now, scientists are eating their words—and trying to catch up. Since December, several variants have been analyzed, each having five or more mutations that change proteins compared to the original strain. Two global variants have received attention in the news, the UK strain (officially known as B 1.1.7) and the South African strain (B 1.351). Evidence suggests that the UK strain is particularly effective at transmitting from one host to another; it seems to be doubling every 10 days in the U.S. even as overall COVID cases are declining. The good news is that vaccines still appear to be very effective at preventing cases of the UK variant.

The South African variant does not seem to be increasing at the same rate in the U.S., which is good, as it seems to have mutations such as one called “Eek” that may allow it to evade our immune system. In some vaccine trials, the South African variant was able to infect individuals who received a vaccine, as well as individuals who had already recovered from COVID-19. Fortunately, the vaccines still appear to protect against serious illness, even if they are not able to protect against infection completely.

New Mutations in New Variants

As the U.S. has begun to sequence viruses, we are seeing some of the same mutations that have been found in Brazil and South Africa appearing in local variants. A variant in New York City has the Eek mutation, and in Oregon, a new version of the UK strain was found that also carried the Eek mutation. The variants are a moving target: each new mutation may change the ability to infect someone new or evade the immune system.

Two things may have led to the emergence of worrying variants. First, the virus has infected over 100 million people around the globe. While the chances of a new mutation leading to a more successful virus might be rare, 100 million is a lot of lottery tickets. Second, as the number of individuals who have survived COVID-19 rise, this may shift which mutations are beneficial. If no one has any immunity, mutations that allow the virus to escape the immune system will have no advantage. But now that large parts of the population have some immunity, either through previous infection or through vaccination, viruses that have mutations that allow it to escape detection by our immune system will have an advantage over those that do not.

The Future of the COVID-19 pandemic

As vaccines are distributed around the world, it's tempting to hope that we may be able to successfully eradicate the coronavirus. In fact, this is something that we’ve achieved before! Measles has been eliminated within the U.S. for the last 20 years, due to the availability of a highly effective vaccine. Is it possible that COVID-19 will share the same fate as measles?

Unfortunately, this might not be the case—at least in the near future. Most experts agree that it’s likely that the coronavirus will continue to circulate in pockets of the global population. In this scenario, COVID-19 may end up resembling another familiar viral illness, the flu. Our best defense against the flu is to get a yearly vaccine, but the efficacy of these vaccines varies from year to year because of how quickly the flu virus evolves.

There have been over 2.5 million deaths worldwide due to COVID-19, so the prospect that it will continue to circulate and evolve is quite concerning. Continued transmission of the virus will likely lead to the emergence of more viral variants. Could these new variants evolve to escape detection by our immune system and make vaccines less effective? The simple answer is that only time will tell. Because the COVID-19 pandemic is still relatively new, many of these fundamental questions won’t be answered for some time.

One of the most encouraging developments during the COVID-19 pandemic has been the implementation of new vaccine technologies. Both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines use a novel approach in which a genetic blueprint for key parts of the virus is introduced into our cells in order to activate our immune system. One of the biggest advantages with this vaccine technology compared to other established approaches is that the blueprint can be altered and incorporated into new vaccines relatively quickly, meaning that we can adapt our vaccines to new viral strains that emerge in the future. This could prove to be a huge boost in our ability to prevent future COVID-19 outbreaks.

Hope Yet Challenges Ahead

As we inch ever closer to a feeling that we’re near the end to the COVID-19 pandemic, we’re reminded of a large highway sign on Interstate-70 in Colorado as you drive east out of the mountains toward Denver. The sign reads “TRUCKERS YOU ARE NOT DOWN YET, ANOTHER 1 ½ MILES OF STEEP GRADES AND SHARP CURVES TO GO.”

We can see the end of the pandemic in the distance, but there are still many challenges ahead. If we want to safely reach our destination, it’s important that we continue to do everything we can to reduce the spread of the virus by wearing masks, washing our hands routinely, practicing physical distancing, and limiting our close contacts. If we continue to do our part, this will give us time to vaccinate people in the U.S. and around the globe and hopefully limit the emergence of new viral variants.