Because of a recent donation of documents and textiles related to Hmong refugees in Decorah, student workers in Luther’s Anthropology Lab are getting hands-on experience cataloging a brand-new collection. And as they come to understand the donated materials and what they mean, they’re gaining context about events unfolding across the world today.

In the twentieth century, the Hmong were a subsistence-farming ethnic minority living in the mountainous regions of Southeast Asia. During the Vietnam War, the CIA recruited them as soldiers and spies to subvert communist forces in Laos. By the end of the war, tens of thousands of Hmong men and boys had been killed fighting for the U.S., and the Laotian communist government vowed to kill any remaining soldiers and their families.

Thousands of Hmong escaped over the Mekong River to refugee camps in Thailand, and many were then spread across the globe in resettlement and asylum programs. Some Hmong refugees faced repatriation to Laos, often unwillingly, since that country continued to loom as a threat to the displaced Hmong. It is a crisis that continues. Even as recently as 2009, the Thai government threatened to return 4,000 Hmong asylum-seekers to Laos, not allowing any foreign government agents or journalists to interview the refugees.

The largest wave of Hmong refugees arrived in the U.S. after the passage of the U.S. Refugee Act of 1980. They came to this country in the midst of a severe global recession, with historically high unemployment—not an easy environment for any newcomer. So as not to pinch state welfare and social support systems, the U.S. scattered them across two dozen states, often breaking up families and frequently moving these tropical immigrants to northern climates. Through enterprise and resilience, the Hmong population in the U.S. has grown to an estimated 200,000-plus, with the largest urban concentration in the Twin Cities.

The Hmong in Decorah

Lutheran churches were common sponsors of Hmong refugees, and a lot of Hmong people immigrated to Decorah under the auspices of Good Shepherd Lutheran and other churches in the area. In the thick of these efforts was Marilyn (Miller) Anderson ’62, who worked in a mostly volunteer capacity to provide language and job training to the new immigrants.

Over her years of close connection with the Hmong in Decorah, Anderson and her mother amassed a lovely collection of Hmong textiles. Recently, she donated these textiles, along with many boxes of refugee-related archival documents, to Luther’s Ethnography Collection. Professor emeritus of anthropology Harv Klevar and his wife, Georgie, also made donations to the textile collection, as did former Development staffer Lilly Womeldorf ’55. And Geraldine Schwartz and Kenneth A. Root, professor emeritus of sociology, contributed to the paper archives. A few Luther students worked with the materials last year, but efforts to organize and investigate the collection have continued in earnest this year, with four dedicated student workers and an anthropology faculty member—Destiny Crider, Anthropology Lab and collections manager and museum studies instructor—to guide them.

One Thursday in November, Anderson showed up at the Anthro Lab like Santa Claus, with a bagful of treasures. She does this periodically, as she uncovers more textiles and documents. She sat down with the students and answered questions while they took notes. She walked them through the new things she had brought, mostly training materials she received as a refugee-services worker.

Toward the end of the visit, she surveyed the files and folders around her. “It’s really wonderful to see it like this,” she said. “This will make it possible to do more.”

Making connections

The four students that Crider hired to work with the Hmong collection are academically diverse, with five majors and seven minors among them. “For this project,” Crider says, “it really works, because we have different lenses and different perspectives from all the cross-majors and minors that can contribute to a cultural study.”

For the first few weeks, Crider had the students bone up on Hmong culture and history. Then, as they acquainted themselves with the collection, they branched into different parts of it according to their inclinations. As Crider says, “This kind of research is going to be particular to each of us—what we’re getting out of it and what we can put into it.”

Elizabeth Wiebke ’19 is organizing new documents and materials within the collection. She’s interested in policy-related questions and connections to current events. Laura Christensen ’18 works with family folders and cross-references newspaper articles to families; she’s eager to learn about local perceptions of the Hmong immigrants and vice versa. Deanna Grelecki ’19 wants to trace how Hmong cultural traditions, particularly marriage ceremonies, changed as refugees moved from Laos to Thailand to the U.S., and she’s using the textiles to investigate this. Thomas Specht ’19 wants to iron out the relationships among the Decorah immigrants—these make the history for him more narrative, more alive—and so he’s working on genealogy and kinship charts.

Asked about the challenges of working with such a new collection, Christensen says, “We have all these different segments of the collection, and the whole point of this work—but also the challenge of it—is to connect them, to connect all these documents and information to the materials and the people, to try to understand their stories. There are a lot of different parts going on right now, and we’re just trying to make sense of all that. We’re asking: What do we do with this collection, and how do we make it meaningful?”

It’s the slow, meticulous work of anthropologists-in-training, and the task can feel overwhelming. Crider reminds them, “There’s a reason I keep saying we’re not responsible for telling this entire story all at once. This is an ongoing process. We’re each trying to find our own way in the story.”

Meanwhile, the students are gaining incredible on-the-job training. They’re problem solving, because, as Crider says, primary sources are messy, and students have to look across multiple sources to make important connections. They’re learning how to work ethically with cultural materials; how to process documents and materials according to the discipline; how to photograph, digitize, and organize a collection; and eventually they’ll learn how to work sensitively and respectfully with anthropological informants.

And, of course, they’re constantly connecting this history with current events, particularly as those events involve refugees.

Says Wiebke, “In our world today, a lot of people are very closed-minded and unaware of a lot of things. I think everyone should have to take a cultural anthropology class. But especially with this collection—this happened in Decorah, Iowa, which is where we’re all living right now, where we go to school, and regardless of whether it directly affects my studies or my future, it impacts me just having the experience of specifically studying this culture and the issues they went through and relating that to the issues of today.”

Grelecki agrees: “It broadens your mind to different perspectives and the fact that there are people who are different from you. As a future educator, that’s something that’s really important to me to instill in younger generations from an earlier age rather than waiting until college—and not everybody takes anthropology in college either—so if you can start incorporating it younger, you can start to eliminate problems that can arise from misunderstanding other people and other cultures, and hopefully that will lead people to become more accepting and create a more open society.”

Specht rounds out the sentiment. “Broadening cultural understanding is really important today, when many people aren’t taking the initiative to understand other cultures. But that understanding is really important in our increasingly globalized world.”

End of an era—but not the end of the story

The refugee-services program in Decorah closed its doors in 1994, and today there is no Hmong population to speak of in town, with almost all of the Hmong who lived in Decorah having moved to Minnesota or Wisconsin. But as the students of the Anthro Lab reconstruct and preserve this history, they begin to make it accessible as a campus and community resource from which people will be able to learn about Decorah’s role in this worldwide event and look to it for lessons good and bad. And since these students are juniors and sophomores, this will be a multiyear project for them, which means they’ll be able to learn and contribute to knowledge in progressively meaningful ways.

Hmong textiles

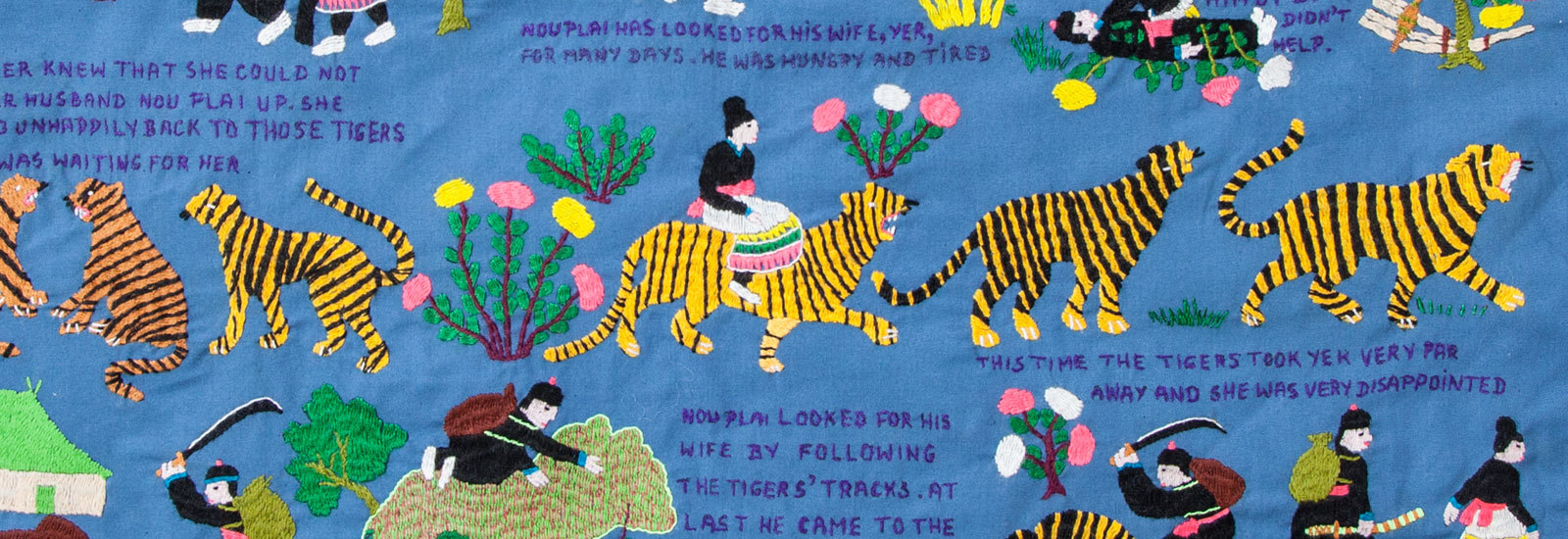

Traditionally, the Hmong embellished clothing and other textiles with decorative needlework, but in the refugee camps they developed pictorial story cloths. With forced idle time, and unable to farm, Hmong women and girls started producing embroidered pieces, like the story cloths, for sale. While the story cloths were a commercial art form, it’s likely that they also served another function—helping a traumatized community process its experience. By detailing the atrocities committed against the Hmong, as well as their difficult journey across the Mekong River, the story cloths both provided proof that the atrocities had happened while also, hopefully, allowing their makers to grieve and mourn and bind some of that mourning into the cloth itself.

The story cloths also helped to share Hmong culture and history with the world. Some of the cloths depict creation stories or folktales, others illustrate rituals or ceremonies, and some present a sort of compendium of animals, among other things.

Traditional Hmong needlework motifs are usually abstract, and the triangles that edge most of the story cloths represent the mountains from which the Hmong came. Technique is adaptable, however, as the detailed, figurative story cloths from the refugee camps show. As the Hmong moved to America, they started to borrow from their adopted culture, sometimes using English captions and featuring Western content, such as Bible stories, crosses, cameras, boom boxes, and televisions. Such changes reflected what was happening in their own lives and also showed how they were adapting their craft to American markets. In addition to the story cloths, Hmong craftswomen also started to make and sell embroidered aprons, bookmarks, pillow covers, and Christmas ornaments, all of which are represented in Luther’s collection.

The Luther College Anthropology Laboratory makes collections available for viewing online at https://anthrodb.luther.edu/index.php/Browse/ethno (use the search term “Hmong” to see the entire textile collection). Inquiries about the collection or making donations should be directed to Destiny Crider in the Anthropology Department.